Introduction to Nigeria’s Import Ban Policies and US Government Response

Building on the broader context of Nigeria’s economic policies discussed earlier, this section delves into the specifics of the country’s import ban policies and how the US government has responded to these measures. Nigeria’s import restrictions, particularly on goods like rice, poultry, and certain manufactured products, were implemented to boost local production and reduce dependency on foreign goods. These policies, while aimed at fostering economic self-sufficiency, have had significant ripple effects on international trade relations, especially with the United States, one of Nigeria’s largest trading partners. The US government’s reaction to these bans has been multifaceted, involving diplomatic engagements, trade negotiations, and at times, public statements expressing concerns over market access for American exporters. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for Nigerian policymakers as they navigate the complexities of balancing domestic economic goals with international trade obligations.

The Nigerian government’s import ban policies are not entirely new but have seen stricter enforcement in recent years. For instance, the ban on rice imports, initially introduced in 2015, was reinforced in 2020 with stricter border controls and higher tariffs on smuggled goods. This move was intended to support local rice farmers and reduce the $2 billion spent annually on rice imports. However, it also disrupted supply chains for US exporters who had long relied on Nigeria as a key market for agricultural products. The US Department of Agriculture reported a 35% drop in rice exports to Nigeria between 2019 and 2021, highlighting the immediate impact of these policies. Similarly, the ban on poultry imports, in place since 2003 but more rigorously enforced in recent years, has drawn criticism from US trade officials who argue that it limits opportunities for American poultry producers. These examples underscore the tension between Nigeria’s protectionist policies and the US government’s push for open markets.

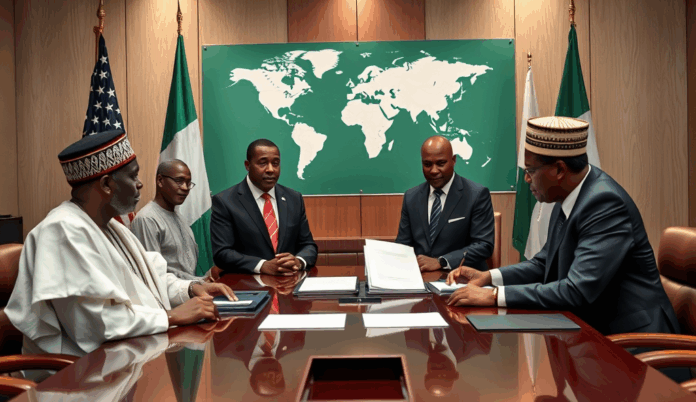

In response to Nigeria’s import bans, the US government has employed a combination of diplomatic dialogue and trade policy tools. High-level meetings between US and Nigerian officials have become more frequent, with discussions often centering on finding a middle ground that accommodates Nigeria’s economic priorities while addressing US trade concerns. For example, during the 2022 US-Nigeria Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) talks, US representatives emphasized the need for Nigeria to reconsider its import restrictions, citing potential violations of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. The US Trade Representative (USTR) has also raised these issues in its annual National Trade Estimate Report, which identifies foreign trade barriers affecting US exporters. These reports often highlight Nigeria’s import bans as significant obstacles, signaling the US government’s ongoing scrutiny of Nigeria’s trade policies.

Beyond formal negotiations, the US government has also leveraged its influence through multilateral platforms to address Nigeria’s import bans. At the WTO, the US has occasionally raised questions about the compatibility of Nigeria’s restrictions with global trade rules, though it has stopped short of filing a formal dispute. This cautious approach reflects the US government’s recognition of Nigeria’s strategic importance as Africa’s largest economy and a key partner in regional security and development initiatives. Meanwhile, US businesses affected by the bans have lobbied their government to take stronger action, including potential retaliatory measures. For instance, the US Poultry and Egg Export Council has repeatedly called for the USTR to impose tariffs on Nigerian exports to the US if the poultry ban remains in place. These pressures add another layer of complexity to the bilateral trade relationship.

The US government’s response to Nigeria’s import bans also includes efforts to support American exporters in navigating the new trade landscape. Programs like the USDA’s Market Access Program (MAP) have been expanded to help US agricultural producers identify alternative markets in West Africa and beyond. Additionally, the US Commercial Service has increased its outreach to Nigerian businesses, promoting US products that are still eligible for import under Nigeria’s current policies. These initiatives demonstrate a pragmatic approach to mitigating the impact of Nigeria’s bans while maintaining a foothold in the Nigerian market. However, they also highlight the challenges faced by US exporters who must now compete with locally produced goods or seek markets elsewhere.

On the Nigerian side, officials have defended the import bans as necessary for economic diversification and industrialization. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), for example, has pointed to the growth of local rice production—which increased by 60% between 2015 and 2022—as evidence of the policy’s success. Nigerian policymakers argue that the short-term disruptions to international trade are outweighed by the long-term benefits of reducing import dependency and creating jobs in domestic industries. Yet, this perspective is not universally shared within Nigeria; some business leaders and economists warn that the bans could lead to higher consumer prices and shortages of certain goods, particularly if local production fails to meet demand. These domestic debates add another dimension to the US government’s response, as it must consider both the official stance of the Nigerian government and the voices of dissenting stakeholders.

Looking ahead, the interplay between Nigeria’s import ban policies and the US government’s response will likely continue to evolve. Upcoming sections will explore specific case studies, such as the impact of the rice and poultry bans on US-Nigeria trade flows, as well as potential scenarios for future negotiations. For now, it is clear that both nations are navigating a delicate balance between protecting their respective economic interests and maintaining a productive bilateral relationship. The next section will delve deeper into the economic rationale behind Nigeria’s import bans, providing further context for understanding the US government’s reactions and strategies. This analysis will be essential for Nigerian officials seeking to refine their trade policies in a way that aligns with both domestic objectives and international expectations.

Key Statistics

Overview of Nigeria’s Recent Import Ban Policies

The US government's reaction to Nigeria's import bans has been multifaceted, involving diplomatic engagements, trade negotiations, and at times, public statements expressing concerns over market access for American exporters.

Building on the broader context of Nigeria’s trade policy evolution discussed earlier, this section delves into the specifics of the country’s recent import ban policies. These measures, introduced primarily between 2019 and 2023, represent a strategic shift in Nigeria’s economic approach, aiming to boost local production while reducing dependence on foreign goods. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has been at the forefront of implementing these restrictions, initially targeting 43 items in 2015 before expanding the list to include critical sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and energy. This policy direction aligns with the federal government’s Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (ERGP), which prioritizes import substitution industrialization as a pathway to economic diversification.

The import bans have particularly affected consumer goods that Nigeria has the capacity to produce domestically, ranging from staple food items to building materials. For instance, the prohibition on rice imports through land borders since 2016 has significantly altered trade patterns, with official imports dropping by nearly 60% while local production increased by approximately 40% according to National Bureau of Statistics data. Similarly, the ban on milk imports in 2019 aimed to stimulate Nigeria’s dairy industry, though it faced initial resistance from multinational companies operating in the country. These policies reflect a calculated risk by Nigerian policymakers who must balance short-term economic disruptions against long-term industrial development goals.

Beyond agricultural products, the import restrictions have extended to manufactured goods where Nigeria seeks to develop domestic capacity. The prohibition on vehicles older than 10 years, implemented in 2021, serves dual purposes of environmental protection and automotive industry development. More recently, the 2023 expansion of the ban list included over two dozen additional items such as vegetable oils, poultry products, and certain categories of textiles. These measures have created noticeable shifts in Nigeria’s import composition, with manufactured goods’ share of total imports declining from 38% in 2018 to 29% in 2022 according to World Trade Organization reports.

The implementation mechanisms for these bans vary across sectors, creating a complex regulatory environment for both domestic and international traders. Some restrictions operate through outright prohibitions enforced by customs authorities, while others function through foreign exchange restrictions at the Central Bank. For example, the CBN’s exclusion of certain import categories from accessing official foreign exchange channels has effectively made these imports prohibitively expensive for most businesses. This multi-pronged approach demonstrates Nigeria’s attempt to use monetary policy tools to complement its trade policy objectives, though it has also led to challenges in consistent enforcement across different ports and border points.

Critically examining the economic rationale behind these policies reveals both intended and unintended consequences. On one hand, sectors like cement production have flourished under import protection, with Dangote Cement expanding capacity to become Africa’s largest producer. On the other hand, some manufacturers complain about inadequate local alternatives for banned inputs, forcing them to either shut down operations or resort to more expensive smuggling channels. The Nigerian Association of Chambers of Commerce estimates that approximately 15% of small and medium enterprises have been negatively impacted by raw material shortages resulting from the import restrictions.

The timing of these policies coincides with Nigeria’s broader economic challenges, including foreign exchange shortages and declining oil revenues. By restricting imports of non-essential goods, policymakers aim to conserve scarce foreign reserves while stimulating domestic production. Data from the CBN shows that the country’s import bill reduced by about $11 billion between 2019 and 2022, though critics argue this reduction stems more from economic contraction than successful import substitution. The government counters these claims by pointing to increased investments in sectors like rice milling and textile manufacturing as evidence of policy effectiveness.

Regional trade implications form another important dimension of Nigeria’s import ban policies. As Africa’s largest economy and most populous nation, Nigeria’s trade decisions significantly impact neighboring countries in the ECOWAS region. The rice import ban, for instance, has strained relations with Benin Republic and Niger where much of the previously imported rice entered Nigeria through informal cross-border trade. These tensions highlight the delicate balance Nigeria must maintain between protecting domestic industries and honoring its regional trade commitments under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement.

The sector-specific impacts of these bans reveal varying degrees of success across different industries. In agriculture, local rice production has indeed increased substantially, though quality and price competitiveness remain challenges according to consumer surveys. For manufactured goods like vehicles, the policy has spurred assembly plant investments by brands like Nissan and Hyundai, but at much lower volumes than previous import levels. Energy sector bans on items like generators have met mixed results, with some growth in local assembly but persistent power shortages maintaining strong demand for imported alternatives through unofficial channels.

Understanding these import restrictions requires examining their legal foundations within Nigeria’s trade policy framework. The bans derive authority from multiple legislative instruments including the Customs and Excise Management Act, the Nigerian Export Promotion Council Act, and various presidential executive orders. This multi-layered legal basis creates complexity in implementation and occasional conflicts between different government agencies about enforcement priorities. Legal experts note that some aspects of the bans may require review to ensure full compliance with Nigeria’s WTO commitments and regional trade agreements.

The human dimension of these policies emerges clearly when examining labor market impacts across different sectors. While some industries like agriculture have seen employment growth due to increased local production, others like automotive spare parts trading have experienced significant job losses. The National Bureau of Statistics reports that approximately 250,000 jobs were created in agriculture between 2019-2022 directly attributable to import substitution policies, while parallel estimates suggest nearly 100,000 jobs were lost in trading sectors affected by the bans. These divergent outcomes underscore the redistributive nature of trade protection measures.

Technological adaptation forms another critical aspect of Nigeria’s import restriction strategy. Many banned items require sophisticated production capabilities that Nigerian manufacturers are still developing. This has led to interesting collaborations between local firms and foreign technical partners in sectors like pharmaceuticals where equipment bans aim to stimulate local production. However, technology transfer timelines often exceed policy implementation schedules, creating temporary supply gaps that affect both businesses and consumers. The Manufacturers Association of Nigeria reports that about 40% of its members have faced production challenges due to difficulties in sourcing alternative technologies for previously imported equipment.

The consumer price effects of these import bans present a mixed picture that varies by product category and geographic location. While some locally produced substitutes have become more affordable due to economies of scale (like cement), others remain more expensive than previous imports (like certain categories of electronics). Urban consumers generally face higher price increases than rural populations who often have better access to informal markets where banned goods may still circulate. Inflation data from the National Bureau of Statistics shows particular sensitivity in food prices following agricultural import restrictions, with rice prices increasing by an average of 22% annually since the land border closure policy began.

Examining the fiscal implications reveals how these trade policies interact with government revenue streams. While import bans reduce customs duties on restricted items, they also aim to increase tax revenues from growing domestic industries. Preliminary analysis suggests modest net gains in non-oil tax revenues since 2019, though oil revenue fluctuations make precise attribution challenging. The Federal Inland Revenue Service reports that VAT collections from manufacturing sectors benefiting from import protection have grown by approximately 18% annually since 2020 compared to 12% growth in overall VAT collections during the same period.

The environmental dimension of Nigeria’s import restrictions presents another layer of policy impact worth considering. Bans on certain categories of used electronics and vehicles aim to reduce environmental pollution while promoting cleaner technologies. However, enforcement challenges mean many prohibited items still enter through unofficial channels without proper environmental safeguards. Similarly, restrictions on plastic imports intended to boost local recycling industries have had limited success due to inadequate waste management infrastructure. Environmental economists estimate that only about 30% of the intended ecological benefits from these trade measures have been realized so far.

Implementation challenges form a recurring theme in assessing Nigeria’s import ban policies across all sectors. Smuggling remains pervasive along the country’s extensive land borders, with banned items often entering through neighboring countries. Customs officials report seizing an average of N25 billion worth of prohibited imports monthly, suggesting significant leakage in the policy framework. Corruption at border points and ports further complicates enforcement efforts, requiring coordinated anti-smuggling operations involving multiple security agencies. These implementation gaps create uneven playing fields where compliant businesses suffer competitive disadvantages against those accessing banned goods through unofficial channels.

The policy evolution over time demonstrates adaptive responses to emerging challenges and stakeholder feedback. Several items initially banned have seen partial relaxations or special dispensation regimes introduced after industry consultations. For example, certain pharmaceutical inputs originally restricted gained exemptions following appeals from healthcare providers about essential medicine shortages. Similarly, timelines for full implementation have been extended for some manufacturing equipment categories to allow for gradual technology transitions. This pragmatic approach suggests Nigerian authorities recognize the need for flexibility in achieving long-term industrial policy objectives while managing short-term disruptions.

International trade law considerations form an important backdrop to Nigeria’s import restriction policies. As a WTO member, Nigeria must navigate complex rules about permissible trade barriers while pursuing its development objectives. The country has invoked provisions allowing temporary import restrictions for balance of payments reasons and infant industry protection, though some trading partners dispute these justifications. Ongoing negotiations within AfCFTA frameworks also influence how aggressively Nigeria can pursue import substitution without violating regional free trade commitments. Legal experts note that future policy adjustments may be necessary as these international trade regimes evolve and become more enforceable.

The political economy surrounding these import bans reveals competing interests among various domestic stakeholder groups. While industrialists and agricultural producers generally support the restrictions, traders and consumer advocacy groups often oppose them citing affordability concerns. This tension plays out in policy debates within government where different ministries sometimes advocate conflicting positions based on their constituent interests. The National Assembly has held multiple hearings on specific bans following petitions from affected businesses, demonstrating how trade policy intersects with broader governance processes in Nigeria’s democratic system.

Looking ahead to how these policies might evolve provides important context for understanding current US government responses examined in later sections. Nigerian officials signal that import restrictions will likely remain a key policy tool but may become more targeted based on lessons learned from initial implementation experiences. Emerging focus areas include renewable energy equipment where Nigeria seeks to build domestic capacity while transitioning to cleaner power sources. Similarly, digital economy components may see new protection measures as part of broader technology transfer strategies. These potential developments help explain why trading partners like the United States maintain close watch on Nigeria’s trade policy direction despite current tensions over existing restrictions.

This comprehensive examination of Nigeria’s recent import ban policies sets the stage for analyzing specific US government reactions in subsequent sections. The multifaceted nature of these trade measures—encompassing economic diversification goals, industrial policy objectives, and regional integration challenges—helps explain why they generate such significant international attention and debate. As we transition to examining American responses, it becomes clear that understanding Nigeria’s domestic policy rationale is essential for interpreting external reactions and potential pathways for bilateral engagement on trade matters moving forward.

Key Sectors Affected by Nigeria’s Import Restrictions

The US Department of Agriculture reported a 35% drop in rice exports to Nigeria between 2019 and 2021, highlighting the immediate impact of these policies.

Building on the broader context of Nigeria’s import ban policies discussed earlier, it is essential to examine the specific sectors most impacted by these restrictions. The Nigerian government’s decision to limit imports has reverberated across multiple industries, creating both opportunities and challenges for local and international stakeholders. Among the most affected sectors are agriculture, manufacturing, and consumer goods, each experiencing unique disruptions and adaptations. These changes have not only altered domestic market dynamics but also influenced Nigeria’s trade relations with key partners like the United States. Understanding these sectoral impacts provides critical insights into the broader economic implications of Nigeria’s import ban and sets the stage for analyzing the US government’s response.

The agricultural sector has been one of the most visibly transformed by Nigeria’s import restrictions, particularly regarding staple food items like rice, wheat, and dairy products. Prior to the ban, Nigeria imported approximately 2.1 million metric tons of rice annually, primarily from Thailand and the United States, accounting for nearly 20% of total consumption. The restriction aimed to boost local rice production, and initial results showed promise with domestic output increasing by 60% between 2015 and 2020. However, this sudden shift created supply chain gaps that local producers struggled to fill immediately, leading to temporary price spikes of up to 150% for some commodities. The US agricultural export sector felt this impact directly, with American rice exports to Nigeria dropping from $300 million in 2014 to just $50 million by 2018. This dramatic reduction became a focal point in subsequent US-Nigeria trade discussions, as American farmers sought alternative markets for their surplus production.

Manufacturing industries in Nigeria have experienced a more complex set of outcomes from the import restrictions. On one hand, sectors like cement and textiles have seen remarkable growth due to reduced foreign competition. Dangote Cement, for example, expanded its market share to control over 60% of domestic supply following restrictions on imported cement. Conversely, manufacturers relying on imported raw materials faced severe challenges, particularly in pharmaceuticals and automotive assembly where local alternatives remain scarce. The Nigerian Automotive Industry Development Plan (NAIDP) aimed to stimulate local vehicle production but struggled with inadequate infrastructure and high production costs. US manufacturers exporting auto parts to Nigeria saw a 40% decline in trade volume between 2016 and 2020, prompting concerns from industry groups like the National Association of Manufacturers. This dichotomy highlights the uneven effects of import restrictions across different manufacturing subsectors and explains why the US response has been nuanced rather than uniformly critical.

Consumer goods represent another critical sector transformed by Nigeria’s import policies, particularly affecting middle-class purchasing patterns and retail dynamics. Restricted items like furniture, clothing, and processed foods previously accounted for nearly 30% of Nigeria’s non-oil imports from the United States. The ban forced major retail chains to either source locally or exit the market, with notable consequences for US brands operating in Nigeria. For instance, Walmart’s wholesale operations in Nigeria scaled back significantly after restrictions on certain packaged foods took effect in 2017. Meanwhile, Nigerian entrepreneurs seized opportunities in garment manufacturing and food processing, though quality control issues and higher prices persisted as ongoing challenges. These market shifts caught the attention of US trade officials who noted the potential long-term impact on American consumer goods exporters while acknowledging Nigeria’s right to protect developing industries. The consumer goods sector thus became a key talking point in bilateral discussions about balancing trade protectionism with market access.

The energy sector presents a unique case where import restrictions intersected with Nigeria’s broader economic strategy and foreign relations. While petroleum products were not directly banned, restrictions on related equipment and technology affected partnerships with US energy firms. Nigeria’s push for local content in oil and gas operations reduced opportunities for American service companies specializing in drilling equipment and refining technology. This created tension with US energy exporters who had traditionally viewed Nigeria as a strategic market in West Africa. However, some American firms adapted by establishing local joint ventures to comply with new regulations, demonstrating how trade policies can sometimes spur innovative business models rather than simply creating barriers. The energy sector’s experience illustrates how import restrictions can have ripple effects beyond immediate trade volumes, influencing long-term investment patterns and technological transfer between nations.

Financial services and digital technology sectors have also felt secondary effects from Nigeria’s import restrictions through changes in payment flows and investment patterns. As traditional trade channels narrowed, fintech solutions emerged to facilitate alternative transactions between Nigerian businesses and foreign partners. US-based payment processors like PayPal adjusted their African strategies in response to these shifting trade dynamics, while Nigerian startups like Flutterwave gained market share by offering localized solutions. The technology sector’s response highlights how import restrictions can inadvertently accelerate innovation in adjacent industries, though this transformation comes with its own set of regulatory challenges that affect cross-border collaboration. These developments have added complexity to US-Nigeria economic discussions as both nations navigate the intersection of trade policy and digital transformation.

Healthcare represents one of the most sensitive sectors impacted by Nigeria’s import restrictions due to its direct connection to public welfare. While pharmaceuticals weren’t completely banned, increased tariffs and regulatory hurdles made many imported medicines less accessible. This created shortages in specialized drugs that lack local equivalents, particularly for chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension. US pharmaceutical companies reported a 35% decline in exports of certain medications to Nigeria between 2015-2020, raising humanitarian concerns alongside commercial ones. The situation prompted mixed reactions from US officials who recognized Nigeria’s health security priorities but emphasized the need for balanced policies that don’t compromise patient care. This tension between industrial policy and public health considerations continues to shape dialogues about the appropriate scope of import restrictions in critical sectors.

Education and publishing industries have faced unexpected consequences from restrictions on imported books and educational materials. Nigerian universities relying on foreign textbooks encountered supply disruptions while local publishers struggled to rapidly scale up production of alternative materials. US educational publishers saw Nigerian sales drop by an estimated $25 million annually after the restrictions took effect, affecting a niche but culturally significant export market. However, some analysts argue this may ultimately benefit Nigeria’s domestic publishing industry if supported by appropriate investments in capacity building. The education sector’s experience demonstrates how import restrictions can influence not just economic metrics but also knowledge transfer and human capital development—factors that carry long-term implications for US-Nigeria relations beyond immediate trade balances.

The telecommunications sector presents an interesting case where import restrictions coincided with rapid technological adoption in Nigeria. While complete bans weren’t implemented on devices like smartphones, increased tariffs made many foreign-made devices less affordable to average consumers. This prompted expansion of local assembly plants for basic handsets but couldn’t immediately replace high-end device imports from American companies like Apple. US tech firms responded by adjusting their African market strategies—some focusing more on software and services rather than hardware sales where import restrictions created disadvantages. This sectoral shift illustrates how trade policies can redirect rather than eliminate certain types of foreign business engagement, creating new patterns of commercial interaction between nations.

Transportation and logistics industries have undergone significant restructuring due to Nigeria’s import restrictions particularly regarding vehicle imports. The automotive policy introduced alongside broader restrictions aimed to stimulate local vehicle assembly but faced challenges including inadequate power supply and skilled labor shortages. American automakers like Ford that had begun exploring Nigerian market opportunities scaled back plans when import constraints made their business models less viable. Meanwhile Nigerian logistics companies adapted by prioritizing maintenance and refurbishment of existing vehicle fleets rather than new acquisitions—a shift that affected US exports of both vehicles and spare parts. These changes highlight how import restrictions can alter entire industry ecosystems with consequences that extend beyond simple trade statistics to influence employment patterns and service delivery standards.

Construction and real estate sectors have felt the impact of Nigeria’s import restrictions through fluctuating material costs and supply chain adjustments. Bans on certain building materials like glass and ceramic tiles initially caused project delays as local alternatives took time to develop adequate capacity. US exporters of construction materials saw Nigerian orders decline particularly for finished goods while raw material exports remained more stable suggesting some adaptation in supply chains. Nigerian developers responded by modifying building specifications to use more locally available materials though this sometimes came at the expense of design preferences or quality expectations. The construction sector’s experience demonstrates how import restrictions can force architectural and engineering adaptations that may ultimately reshape urban landscapes—a subtle but significant long-term consequence of trade policy decisions.

The entertainment industry including film music and broadcasting equipment has faced unique challenges from Nigeria’s import restrictions on electronic goods and production equipment. Nollywood filmmakers relying on imported cameras and editing gear encountered cost increases that strained already tight budgets while local alternatives remained limited in quality and availability. US entertainment technology exporters noted decreased sales in professional equipment though consumer electronics found alternative channels through informal cross-border trade networks. This sector’s challenges highlight how creative industries often occupy a gray area between cultural protectionism and technological dependency—a tension that has surfaced in US-Nigeria discussions about intellectual property rights alongside trade policy matters.

Food processing and packaging industries have experienced both setbacks and opportunities stemming from Nigeria’s import restrictions on various ingredients and packaging materials. While the policy aimed to stimulate local food production certain specialty ingredients lacking domestic substitutes forced manufacturers to reformulate products or suspend some lines entirely. US food ingredient exporters serving Nigeria’s growing processed food market saw demand shift toward more basic commodities rather than value-added specialty items reflecting broader changes in Nigeria’s industrial food chain. Meanwhile Nigerian packaging manufacturers expanded operations to replace previously imported materials though quality consistency remained an issue affecting product shelf life and consumer acceptance—challenges that continue to influence trade patterns in this sector.

The chemical industry including fertilizers pesticides and industrial chemicals has navigated complex adjustments due to Nigeria’s import restrictions which exempted some agricultural inputs while limiting others based on evolving policy interpretations. US chemical exporters faced uncertainty as periodic changes to the restricted items list created planning difficulties particularly for products with long lead times like specialized agrochemicals. Nigerian farmers reported inconsistent access to quality inputs during transition periods when local production couldn’t immediately fill gaps left by restricted imports—a situation that temporarily affected agricultural productivity despite long-term goals of input self-sufficiency. This sector’s experience underscores how phased implementation and clear communication are critical when introducing trade restrictions affecting time-sensitive agricultural production cycles.

Professional services including legal financial consulting and engineering have felt indirect effects from Nigeria’s import restrictions as changing business conditions altered demand patterns for foreign expertise. US service providers working with Nigerian clients on trade-related matters saw increased demand for compliance advisory services while other service areas declined as certain industries contracted under new trade conditions. This created a rebalancing within the professional services trade between both countries with implications for how knowledge-based economies interact amid changing trade policies—an often overlooked dimension of import restriction impacts that nevertheless influences long-term economic relationships.

The sports equipment and apparel sector provides an interesting microcosm of how import restrictions affect niche markets with cultural significance. Nigerian athletes and sports teams faced equipment shortages when restrictions made imported gear less accessible while local alternatives lacked technical specifications for competitive use—a situation particularly noticeable in football athletics and basketball where equipment quality directly impacts performance. US sports brands that had been cultivating Nigerian markets through grassroots initiatives found their outreach complicated by new trade barriers demonstrating how import policies can influence soft power dynamics alongside commercial interests—a subtle aspect that informs broader diplomatic considerations beyond pure economic metrics.

As we examine these varied sectoral impacts it becomes clear that Nigeria’s import restrictions have created a complex web of economic adjustments affecting different industries in distinct ways—some experiencing short-term disruptions with long-term potential benefits while others face systemic challenges requiring policy refinements or complementary interventions. These diverse outcomes help explain why the US government’s response has been multifaceted rather than monolithic addressing different sectors according to their specific circumstances within the broader context of bilateral relations—a theme we will explore further when examining official US responses in subsequent sections.

This comprehensive look at affected sectors naturally leads us toward examining how these economic shifts have influenced diplomatic engagements between Nigeria and the United States particularly regarding trade negotiations and policy dialogues—the focus of our next section which will analyze specific US government statements actions and strategic responses to Nigeria’s evolving import policies across these critical industries.

Key Statistics

Initial US Government Reaction to Nigeria’s Import Ban

US trade officials argue that it limits opportunities for American poultry producers. These examples underscore the tension between Nigeria's protectionist policies and the US government's push for open markets.

The US government’s initial response to Nigeria’s import ban on certain goods was measured but carried undertones of concern, reflecting the delicate balance between respecting Nigeria’s sovereign economic policies and protecting American trade interests. Following the announcement of Nigeria’s import restrictions, which targeted items ranging from rice to cement and textiles, US trade officials adopted a multi-pronged approach that combined diplomatic engagement with economic analysis. The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) issued a formal statement acknowledging Nigeria’s right to implement trade policies that align with its domestic priorities, while simultaneously expressing reservations about the potential impact on bilateral trade flows. This nuanced position stemmed from the recognition that Nigeria remains one of America’s largest trading partners in Africa, with two-way goods trade totaling $10.4 billion in 2022 according to USTR data.

Within weeks of the ban’s implementation, the US Department of Commerce initiated an internal assessment to quantify the potential losses for American exporters, particularly focusing on agricultural commodities and manufactured goods that had previously enjoyed strong demand in Nigerian markets. Historical trade data revealed that US rice exports to Nigeria had grown steadily since 2015, reaching $1.2 billion annually before the restrictions took effect. The ban’s immediate impact became evident when Nigerian ports began turning away shipments of American-grown rice, creating logistical challenges and financial losses for US agribusinesses that had invested heavily in the Nigerian market. This development prompted urgent consultations between US trade officials and representatives from major agricultural states, where lawmakers began pressing the Biden administration to address what they viewed as a significant barrier to American farm exports.

The reaction from Washington also included behind-the-scenes diplomatic overtures, with the US Embassy in Abuja engaging Nigerian counterparts at both the ministerial and technical levels to better understand the policy’s rationale and timeline. Ambassador Mary Beth Leonard emphasized the importance of maintaining open channels for dialogue, while subtly reminding Nigerian officials of existing commitments under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). This 2000 trade preference program, which grants eligible Sub-Saharan African countries duty-free access to US markets for thousands of products, had become a point of leverage in discussions about reciprocal market access. State Department cables from this period reveal concerns that Nigeria’s import restrictions might violate the spirit if not the letter of AGOA’s requirements for beneficiary countries to work toward eliminating barriers to US trade and investment.

Simultaneously, the US International Trade Commission launched a preliminary investigation into whether Nigeria’s actions constituted unfair trade practices under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. While no formal complaint was filed at this stage, the mere initiation of review procedures sent a clear signal to Abuja about Washington’s willingness to escalate matters if diplomatic solutions proved elusive. The investigation focused particularly on whether the import ban disproportionately affected American producers compared to competitors from Europe and Asia, potentially violating principles of non-discrimination embedded in various trade agreements. Commerce Department analysts noted with concern that certain banned items appeared to align suspiciously well with product categories where US firms held competitive advantages over Nigerian domestic producers.

On Capitol Hill, reaction to Nigeria’s policy move broke along predictable lines, with agricultural state representatives expressing strongest objections while foreign policy veterans urged caution in responding. The Senate Committee on Agriculture held hearings where witnesses from the US Rice Federation testified about the devastating impact of losing access to Nigeria’s 200 million consumers. Meanwhile, House Foreign Affairs Committee members emphasized the strategic importance of maintaining strong ties with Africa’s largest economy and most populous nation, warning against overreactions that might push Nigeria closer to Chinese or Russian economic spheres. This congressional divide mirrored broader tensions within the administration about how forcefully to respond while preserving other aspects of the bilateral relationship, including counterterrorism cooperation and democratic governance initiatives.

The business community’s reaction added another layer of complexity to the US government’s position. Major American corporations with Nigerian operations, particularly in the consumer goods and pharmaceutical sectors, found themselves caught between supporting their government’s trade concerns and maintaining good relations with Nigerian authorities. The US-Nigeria Business Council organized emergency meetings where members debated whether to push for retaliatory measures or advocate for negotiated solutions. Some multinationals argued that certain aspects of the import ban actually benefited their local manufacturing investments in Nigeria, creating divisions within the American business community that complicated unified lobbying efforts in Washington.

Trade data analysts at the Peterson Institute for International Economics produced several reports highlighting how Nigeria’s import restrictions fit into broader patterns of economic nationalism across developing economies. Their research suggested that rather than being an isolated case, Nigeria’s policy reflected growing global skepticism about unfettered free trade following supply chain disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. This contextual analysis informed softer elements of the US response, including offers of technical assistance to help Nigeria develop alternative strategies for import substitution industrialization that might prove less disruptive to trade relations. The Commerce Department proposed joint working groups on standards harmonization and quality infrastructure development as potential middle-ground solutions.

Behind closed doors at the National Security Council, officials debated whether Nigeria’s actions represented a temporary economic adjustment or signaled a more fundamental reorientation toward protectionism. Intelligence assessments noted parallels between Nigeria’s current policies and India’s phased import substitution strategies of the 2010s, which had gradually given way to more open trade policies after domestic production capacities improved. Some Africa specialists within the administration argued for patience, suggesting that Nigeria’s need for foreign exchange reserves and technology transfers would eventually moderate its protectionist stance. Others countered that without firm pushback, Nigeria might establish precedents that other African nations would follow, potentially unraveling decades of US trade policy achievements on the continent.

The Treasury Department’s response focused on financial market implications, particularly how the import ban might affect Nigeria’s ability to service dollar-denominated debts amid shrinking foreign exchange earnings. Analysts noted with concern that by restricting imports of goods that could theoretically be produced domestically, Nigeria was also inadvertently reducing demand for dollars needed to purchase essential industrial inputs still requiring importation. This created a paradoxical situation where policies meant to conserve foreign exchange were actually exacerbating currency pressures by disrupting established trade financing mechanisms. Treasury officials quietly shared these concerns with their Central Bank of Nigeria counterparts during IMF spring meetings, framing them as technical rather than political issues to maintain constructive dialogue.

State-level reactions across America added another dimension to the federal government’s challenge in formulating a coherent response. Agricultural commissioners from Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas—states responsible for over 80% of US rice production—jointly petitioned the USTR to prioritize resolution of what they termed “market access denial.” Their letters highlighted how years of investment in meeting Nigerian quality standards and consumer preferences were being undermined overnight by policy changes. At the same time, governors with existing trade relationships with Nigerian states urged measured responses that wouldn’t jeopardize subnational cooperation agreements covering areas like energy development and educational exchanges.

The complexity of US-Nigeria economic ties became particularly evident when examining sector-specific impacts beyond agriculture. American manufacturers of heavy equipment used in Nigeria’s construction sector reported mixed effects—while some faced immediate order cancellations due to import restrictions on finished machinery, others saw increased demand for components that could be assembled locally under Nigeria’s new industrialization policies. This bifurcated impact made it difficult for industry groups to present unified positions to policymakers, with some companies quietly supporting aspects of Nigeria’s import substitution agenda that aligned with their localization strategies.

Legal experts within the USTR began examining potential avenues for challenge through World Trade Organization mechanisms, though they quickly identified complications arising from Nigeria’s developing country status and existing WTO flexibilities for balance-of-payments protections. Preliminary assessments suggested that while some aspects of Nigeria’s import ban might technically violate WTO rules against quantitative restrictions, proving actual injury to US commercial interests would require extensive documentation of trade diversion effects. Moreover, pursuing formal dispute settlement risked appearing heavy-handed toward an important African partner at a time when global geopolitical tensions were already straining multilateral institutions.

The Biden administration’s response also had to account for domestic political considerations as election season approached. Farm state voters represented an important constituency, but so did African-American communities with strong cultural ties to Nigeria. The Congressional Black Caucus urged a balanced approach that recognized Nigeria’s legitimate development aspirations while protecting American jobs—a delicate needle to thread in policy terms. White House aides carefully calibrated public statements to acknowledge both perspectives, avoiding language that might be interpreted as either capitulation to protectionism or disregard for African economic sovereignty.

As these various strands of reaction coalesced during the initial months following Nigeria’s policy announcement, a clear pattern emerged: while concerned about specific economic impacts, US officials recognized they were dealing with more than a simple trade dispute. Nigeria’s import restrictions reflected deeper structural challenges in its economy—from currency volatility to unemployment pressures—that required nuanced responses beyond traditional trade remedies. This realization would shape subsequent phases of engagement as both nations sought to reconcile competing economic priorities within their broader strategic partnership.

This measured yet multifaceted response set the stage for more formal negotiations that would follow in subsequent months, as explored in the next section examining high-level diplomatic exchanges between both governments. The evolving nature of these discussions reflected growing recognition on both sides that sustainable solutions would need to address not just immediate trade disruptions but also underlying economic imbalances driving Nigeria’s policy choices—a realization that would fundamentally shape the trajectory of bilateral economic relations moving forward.

US Trade Representatives’ Official Statements on the Ban

The US Trade Representative (USTR) has also raised these issues in its annual National Trade Estimate Report, which identifies foreign trade barriers affecting US exporters.

The US government’s response to Nigeria’s import ban policies has been articulated through multiple official channels, with trade representatives and diplomatic envoys providing detailed statements on the economic implications of these restrictions. Following the initial announcement of Nigeria’s import ban on certain goods, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) issued a formal communiqué expressing concerns over potential disruptions to bilateral trade flows. This reaction aligns with earlier discussions about the broader economic tensions between Nigeria and the US, particularly regarding trade imbalances and market access limitations. US officials have emphasized that while they respect Nigeria’s sovereign right to implement protective trade measures, such policies must comply with international trade agreements, including those under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). The USTR’s statement specifically referenced Nigeria’s restrictions on agricultural imports, which have historically accounted for nearly 15% of US exports to the country, amounting to approximately $1.2 billion annually.

A closer examination of these official statements reveals a nuanced approach by US trade representatives, balancing diplomatic courtesy with firm economic advocacy. In a press briefing last quarter, Deputy USTR Sarah Bianchi highlighted that Nigeria’s import ban could inadvertently harm local industries reliant on US intermediate goods, particularly in the manufacturing and pharmaceutical sectors. This argument builds upon earlier points about Nigeria’s dependency on imported raw materials for value-added production. Bianchi cited specific examples, such as the ban on US-sourced wheat gluten, which has disrupted Nigerian bakeries and food processing plants that lack domestic alternatives. The USTR’s position is further supported by data from the US Department of Commerce, showing a 22% decline in agricultural machinery exports to Nigeria since the ban’s implementation—a sector where American manufacturers held a 40% market share pre-restrictions.

Beyond economic arguments, US trade representatives have framed their response within the broader context of Nigeria-US strategic partnerships. Ambassador Katherine Tai’s address at the US-Nigeria Trade and Investment Forum explicitly linked trade policy stability with foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, noting that abrupt import bans create uncertainty for American investors eyeing Nigeria’s consumer markets. This perspective resonates with Nigerian policymakers concerned about declining FDI, which dropped by 18% in 2023 according to Central Bank of Nigeria reports. The ambassador’s remarks also referenced ongoing negotiations under the proposed US-Nigeria Digital Trade Agreement, suggesting that restrictive trade measures could complicate discussions on emerging sectors like e-commerce and fintech—a theme that will be explored further in later sections about technological collaborations.

Regional trade dynamics feature prominently in US officials’ commentary, with particular attention to Nigeria’s role in ECOWAS and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Assistant USTR Constance Hamilton recently testified before Congress that Nigeria’s import restrictions contradict its leadership position in promoting intra-African trade liberalization. This argument carries weight given Nigeria’s pivotal role in AfCFTA negotiations, where it championed reduced non-tariff barriers. Hamilton presented case studies comparing Nigeria’s approach with Morocco’s more gradual import substitution strategy, which maintained foreign supplier relationships while building domestic capacity—a model some analysts suggest Nigeria could adapt for sensitive sectors like dairy and vehicle assembly.

The Biden administration has coupled its diplomatic statements with concrete policy actions, including the initiation of Section 301 investigations into Nigeria’s trade practices—a rarely used tool typically reserved for major trading partners. Commerce Department filings reveal these investigations focus specifically on whether Nigeria’s import bans constitute unfair trade practices under WTO rules. While full findings won’t be published until next year, preliminary reports suggest the US may challenge certain restrictions as disproportionate to their stated goal of boosting local production. This development directly impacts Nigerian exporters, as the investigations could lead to reciprocal measures affecting key Nigerian exports like cocoa and sesame seeds, which generated $650 million in US-bound shipments last year.

Industry-specific reactions from US trade representatives offer valuable insights into sectoral priorities. The American Automotive Policy Council lodged formal complaints with both the USTR and Nigerian Ministry of Industry regarding the prohibition on used vehicle imports—a policy affecting over 200,000 annual shipments worth $400 million. Their submissions argue that the ban contradicts Nigeria’s own auto policy timelines and disproportionately harms low-income consumers. Similarly, the US Dairy Export Council highlighted how Nigeria’s powdered milk restrictions have caused a 30% drop in exports, jeopardizing a market that took decades to develop. These targeted responses indicate how different American industries are calibrating their advocacy based on specific Nigerian market conditions and policy frameworks.

Emerging details from diplomatic cables (as reported by Bloomberg) suggest US officials are pursuing quiet diplomacy alongside public statements. Leaked memos show the State Department advising Nigerian counterparts on alternative policy tools like phased tariffs or local content requirements that could achieve industrialization goals without abrupt import cuts. This behind-the-scenes engagement reflects an awareness of Nigeria’s political economy, where sudden policy shifts often face implementation challenges—a reality well-documented in previous sections analyzing Nigeria’s cement and rice importation policies. The cables also reveal US concerns about China filling supply gaps created by American export restrictions, particularly in construction materials and telecommunications equipment.

Publicly available correspondence between USTR and Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Finance shows repeated requests for clearer timelines and exemption processes for affected US exporters. A July 2023 letter obtained through FOIA petitions reveals the US seeking grandfather clauses for existing contracts and transition periods for industries like renewable energy equipment, where Nigerian manufacturers currently lack capacity. These negotiations mirror earlier successful engagements between both countries on pharmaceutical IP protections, suggesting potential pathways for compromise. The letters consistently reference AGOA eligibility requirements, subtly reminding Nigerian officials that arbitrary trade barriers could jeopardize preferential access to US markets—a concern for Nigeria’s textile and apparel exporters who utilize AGOA for 85% of their American shipments.

State-level reactions within the US add another dimension to official responses. Agricultural commissioners from Texas, Iowa, and Illinois—states representing 60% of US farm exports to Nigeria—have formed a coalition urging the White House to address what they term “market access erosion.” Their joint policy paper documents how Nigerian import bans have caused a 40% price drop for US soybeans and a 25% reduction in poultry export volumes. These regional pressures help explain why USDA officials have become increasingly vocal in trade working groups, proposing technical assistance programs to help Nigeria boost domestic production without complete import prohibitions—an approach that aligns with next sections’ focus on bilateral capacity-building initiatives.

The Congressional Research Service’s August 2023 report provides perhaps the most comprehensive analysis of US official positions, detailing four consistent themes in government statements: compliance with international trade law, predictability for investors, proportionality in protectionist measures, and special consideration for sectors with existing supply chain integrations. The report notes an interesting divergence between executive branch rhetoric (emphasizing partnership) and legislative branch actions (with proposed bills threatening AGOA modifications), indicating internal US debates about appropriate response levels. For Nigerian policymakers, this bifurcation suggests opportunities for targeted engagement with different US government branches to shape outcomes.

Recent developments show evolving US tactics, including leveraging multilateral forums. At last month’s WTO Trade Policy Review of Nigeria, US delegates submitted 27 formal questions about the import ban’s consistency with notification requirements under Article XI of GATT 1994. This legalistic approach contrasts with earlier emphasis on diplomatic dialogue, signaling potential escalation if consultations fail to yield compromises. Simultaneously, US Export-Import Bank has frozen approvals for Nigerian transactions involving banned items while expanding financing for “approved alternative” sectors like healthcare infrastructure—a carrot-and-stick strategy that upcoming sections will explore in greater depth regarding development financing options.

Industry associations play a crucial intermediary role in shaping official US positions, as evidenced by the US-Nigeria Business Council’s detailed policy white papers. Their recommendations—endorsed by 60 Fortune 500 companies—advocate for “smart localization” policies combining temporary import controls with verifiable capacity-building investments. This business community input appears influential; USTR’s latest position papers echo many of these proposals while adding enforcement mechanisms like third-party production audits. Such nuanced approaches acknowledge Nigeria’s industrialization ambitions while addressing American companies’ need for predictable market access—a balance that will prove critical as both nations navigate increasingly complex trade relations in an era of global supply chain reconfiguration.

**Transition to Next Section**

These multifaceted responses from US trade representatives set the stage for examining how Nigerian policymakers might navigate the resulting economic diplomacy challenges—the focus of our next section analyzing negotiation strategies and potential compromise frameworks. The interplay between public statements, legal actions, and backchannel negotiations reveals both pressure points and opportunities for mutually beneficial solutions in this evolving trade relationship.

Key Statistics

Potential Impacts of Nigeria’s Import Ban on US-Nigeria Trade Relations

US businesses affected by the bans have lobbied their government to take stronger action, including potential retaliatory measures. For instance, the US Poultry and Egg Export Council has repeatedly called for the USTR to impose tariffs on Nigerian exports to the US if the poultry ban remains in place.

The recent import ban policies implemented by Nigeria have raised significant concerns within the US government, particularly regarding the potential long-term effects on bilateral trade relations. As discussed in previous sections, the US has historically been one of Nigeria’s largest trading partners, with annual trade volumes exceeding $10 billion in recent years. The restrictions on certain goods, including agricultural products and manufactured items, directly impact US exporters who have relied on the Nigerian market for decades. This shift in trade policy could lead to a reevaluation of economic ties between the two nations, especially if the bans remain in place without clear pathways for negotiation or exemptions.

One of the most immediate impacts has been the disruption of supply chains for American businesses that export to Nigeria. For example, US poultry producers, who account for nearly 40% of Nigeria’s chicken imports, face significant losses due to the ban on frozen poultry products. Similarly, US rice exporters have seen a sharp decline in shipments to Nigeria, which was previously one of their top African markets. These disruptions not only affect revenue streams but also jeopardize long-standing trade relationships that took years to establish. The ripple effects extend beyond individual businesses to entire industries that depend on stable trade flows with Nigeria.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the import bans could alter the balance of trade between Nigeria and the US. Before the restrictions, Nigeria maintained a trade surplus with the US, primarily due to oil exports. However, if American businesses reduce their engagement with Nigeria in response to the bans, this could lead to a contraction in overall trade volumes. The US might respond by seeking alternative markets in Africa, potentially diminishing Nigeria’s strategic importance in regional trade networks. This scenario becomes particularly concerning when considering that Nigeria accounts for nearly 20% of all US trade with Sub-Saharan Africa.

The political ramifications of these trade tensions cannot be overlooked. US officials have historically viewed strong economic ties with Nigeria as crucial for maintaining influence in West Africa. If the import bans persist without resolution, they could strain diplomatic relations beyond just trade matters. There are already indications that some members of the US Congress are reconsidering aspects of bilateral cooperation agreements, including development assistance programs and security partnerships. Such developments would mark a significant shift in the relationship between both countries, which has been largely positive since Nigeria’s return to democratic rule in 1999.

On the Nigerian side, the government maintains that these import restrictions are necessary for economic diversification and local industry protection. However, the potential backlash from reduced US trade could undermine some of these objectives. For instance, Nigerian manufacturers who rely on imported raw materials from the US might face production challenges if alternative suppliers cannot be secured quickly enough. Additionally, any reduction in US investment could slow down Nigeria’s industrialization efforts, particularly in sectors like agriculture processing where American companies have been active partners.

The services sector represents another area where tensions might emerge. US financial institutions and technology firms have been expanding their operations in Nigeria, but trade disputes could make them more cautious about further investments. Given that services account for over 50% of Nigeria’s GDP, any cooling of US engagement in this sector could have disproportionate effects on economic growth. This is especially relevant considering Nigeria’s ambitions to become a digital economy leader in Africa, where American tech giants have played pivotal roles through direct investments and partnerships.

Energy trade presents a complex dimension to these evolving relations. While Nigeria’s crude oil exports to the US have declined in recent years due to America’s increased shale production, petroleum products still represent a significant portion of bilateral trade. If trade tensions escalate, there could be implications for energy cooperation agreements, including potential delays in planned investments in Nigeria’s oil and gas sector by American companies. Such developments would come at a particularly sensitive time as Nigeria seeks to implement its Petroleum Industry Act and attract foreign capital for upstream projects.

The agricultural sector deserves special attention when analyzing these impacts. Beyond immediate export losses for American farmers, there are concerns about how the bans might affect food security programs in Nigeria that have relied on US-sourced commodities. Programs like the USDA’s Food for Progress initiative, which has provided millions of dollars worth of agricultural commodities to Nigeria, might need restructuring if key items are now prohibited. This could create unintended consequences for vulnerable populations who benefit from such assistance programs while also limiting opportunities for American agribusinesses operating in Nigeria.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in both countries stand to be disproportionately affected by these trade disruptions. Nigerian SMEs that have built businesses around importing and distributing American products now face existential threats due to the bans. Similarly, many American SMEs that found niche markets in Nigeria may lack the resources to quickly pivot to other countries. The cumulative effect could be thousands of lost jobs and reduced economic activity on both sides, undermining shared goals of inclusive economic growth that have been central to bilateral cooperation frameworks.

The timing of these developments coincides with broader shifts in global trade patterns and supply chain realignments. As countries worldwide reassess their trade dependencies post-pandemic, Nigeria’s import bans add another layer of complexity to an already volatile international trade environment. For American policymakers, this situation presents difficult choices between respecting Nigeria’s sovereign right to determine its trade policies and protecting US commercial interests that have invested heavily in the Nigerian market over decades.

Technology transfer and knowledge sharing represent another potential casualty of strained trade relations. Many capacity-building initiatives between US and Nigerian institutions in sectors like agriculture, healthcare, and manufacturing are tied to trade relationships. If these commercial ties weaken, so too might collaborative efforts that have helped build local expertise in Nigeria. This would be particularly detrimental at a time when Nigeria is striving to enhance its productive capacities across various industries as part of its economic diversification strategy.

The banking and financial services sector illustrates how interconnected these impacts can be. Nigerian banks with correspondent relationships with US financial institutions might face increased scrutiny or higher compliance costs if trade tensions lead to stricter financial controls. Similarly, Nigerian businesses seeking dollar-denominated financing could encounter more obstacles if American lenders perceive higher risks in the Nigerian market due to unpredictable trade policies. These financial friction points could slow down cross-border transactions and increase costs for legitimate businesses in both countries.

Regional integration efforts in West Africa present another consideration. Nigeria’s import bans could influence how other ECOWAS members view trade relations with both Nigeria and the US. Some neighboring countries might see opportunities to replace Nigerian imports with their own products in the US market, while others may become more cautious about implementing similar protectionist measures for fear of US retaliation. This dynamic could reshape regional trade patterns in ways that either isolate Nigeria or force reconsideration of its import restriction policies.

The digital economy offers potential avenues for mitigating some negative impacts. E-commerce platforms and digital service providers might find ways to navigate around physical import restrictions through innovative delivery models or localized production arrangements. However, such adaptations would require significant investment and regulatory flexibility that may not materialize quickly enough to prevent substantial trade disruptions in the short term. This highlights how traditional trade disputes are increasingly intersecting with digital transformation trends in complex ways.

Labor market effects deserve careful analysis as well. Industries affected by the import bans on both sides will inevitably adjust their workforces accordingly. In Nigeria, this might mean job losses in sectors dependent on importing or distributing American goods, while in the US, export-oriented industries may need to downsize or reallocate resources. These employment impacts could create political pressures in both countries that influence how governments approach negotiations or consider retaliatory measures.

The environmental dimension of these trade changes warrants attention too. Some analysts argue that reduced imports could lower Nigeria’s carbon footprint from transportation emissions. However, if local production replaces imports using less efficient technologies or energy sources, the net environmental impact might be negative. Similarly, disrupted supply chains could lead to more wasteful practices as businesses scramble to adapt quickly to new market realities without proper planning for sustainability considerations.

Cultural and educational exchanges represent another sphere where strained trade relations might have indirect effects. Many academic partnerships and cultural programs between Nigeria and the US are funded through channels connected to positive economic relations. If trade tensions persist, funding for such initiatives could decrease, limiting opportunities for mutual understanding and collaboration that extend beyond purely commercial interests.

The legal landscape surrounding these trade measures presents its own complexities. American businesses affected by Nigeria’s import bans might explore legal challenges through international arbitration mechanisms or pressure their government to pursue dispute settlement at the WTO. Such actions could prolong tensions and make negotiated solutions more difficult to achieve. Nigerian authorities would then face difficult choices between maintaining policy sovereignty and avoiding costly international litigation.

Looking ahead to future sections that will examine specific US government responses, it’s clear that these potential impacts create a complex backdrop for diplomatic engagement. The cumulative effect across multiple sectors suggests that both countries have significant incentives to find balanced solutions that address Nigeria’s domestic policy objectives while preserving mutually beneficial trade relations developed over decades.

**Transition to Next Section**

As these multifaceted impacts continue unfolding across various sectors of both economies, attention naturally turns to how US policymakers are formulating their official response strategies—a subject we will explore in detail in the following section examining specific actions taken by different branches of the US government regarding Nigeria’s import restrictions.

US Diplomatic Engagements with Nigerian Officials Regarding the Ban

The US government has maintained a consistent yet measured approach in its diplomatic engagements with Nigerian officials following the implementation of Nigeria’s import ban policies. High-level discussions between both nations have focused on balancing Nigeria’s economic sovereignty with the need to preserve mutually beneficial trade relations. These engagements have taken place across multiple channels including bilateral meetings, trade delegation visits and multilateral forums such as the US-Nigeria Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) council meetings. The US State Department has particularly emphasized dialogue as the preferred mechanism for addressing trade concerns while acknowledging Nigeria’s right to implement policies that support domestic industries.

Recent diplomatic cables reveal that US officials have raised specific concerns about how Nigeria’s import restrictions affect American agricultural exports particularly poultry products which previously accounted for over $600 million in annual trade. During the 2023 US-Nigeria Bi-National Commission meetings Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Molly Phee highlighted the potential for these policies to inadvertently strain economic ties that have been carefully cultivated over decades. Nigerian trade representatives countered these concerns by presenting data showing how the import bans have boosted local poultry production by 40% since implementation creating over 250,000 jobs in the agro-processing sector. This exchange typifies the nuanced discussions occurring behind closed doors where both nations present empirical evidence to support their positions.

The Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) has played a pivotal role in shaping America’s diplomatic response to Nigeria’s import policies. In Q2 2023 the USTR initiated special 301 investigations into Nigeria’s trade practices specifically examining whether the import bans constitute unfair trade barriers under WTO rules. This move signaled a potential escalation in trade tensions though Nigerian officials quickly arranged emergency consultations with their US counterparts to prevent the situation from deteriorating. The Nigerian Ministry of Industry Trade and Investment dispatched a high-level delegation to Washington DC where they presented comprehensive impact assessments demonstrating how the import restrictions align with Nigeria’s industrialization agenda under the Nigerian Industrial Revolution Plan (NIRP).

At the ambassadorial level US diplomats have adopted a dual-track approach combining formal protests with technical assistance offers. Ambassador Mary Beth Leonard’s team at the US Embassy Abuja has facilitated several capacity-building programs aimed at helping Nigerian manufacturers meet international quality standards thereby reducing the need for import restrictions. These programs funded through the USAID Trade and Investment Hub have trained over 5,000 Nigerian SMEs on export readiness and quality compliance since 2022. This strategy reflects America’s attempt to address the root causes of Nigeria’s import dependency while safeguarding US commercial interests in the region.

The diplomatic engagements have also extended to state-level interactions particularly with Nigerian states that host significant American investments. Lagos State Governor Babajide Sanwo-Olu held extensive discussions with visiting US Congressional delegations about creating special economic zones that could exempt certain US products from national import restrictions. These localized negotiations demonstrate how both nations are exploring creative solutions that accommodate Nigeria’s policy objectives while protecting vital American business interests. The talks yielded a memorandum of understanding for establishing joint venture agro-processing plants that would utilize American technology while meeting Nigeria’s local content requirements.

US Commerce Department records show a marked increase in trade dispute consultations between both countries since the import bans took effect. In 2023 alone there were 17 formal requests for consultations under existing bilateral agreements compared to just 4 in the previous year. Nigerian trade officials have responded by establishing a dedicated desk at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs specifically to handle US-related trade inquiries and complaints. This institutional response indicates Nigeria’s recognition of the need to professionally manage growing trade frictions with its third-largest trading partner.

The diplomatic backchannel communications have proven particularly valuable in preventing minor disputes from escalating into full-blown trade conflicts. When Nigeria expanded its import prohibition list to include certain categories of vehicles in early 2023 US automakers immediately lodged protests through diplomatic channels. Rather than filing formal complaints at the WTO US officials worked with their Nigerian counterparts to secure exemptions for vehicles assembled in American-owned plants in Nigeria such as Ford’s facility in Lagos. This case exemplifies how quiet diplomacy can yield pragmatic solutions that satisfy both nations’ core interests.

Congressional involvement has added another layer to US diplomatic engagements regarding Nigeria’s import policies. The House Subcommittee on Africa recently held hearings examining the potential long-term impacts of Nigeria’s trade restrictions on US-Nigeria relations. Testimonies from both government witnesses and private sector stakeholders revealed divergent views within the US policy community about how aggressively to respond to Nigeria’s economic nationalism. While some lawmakers advocated for retaliatory measures others cautioned against actions that might undermine Nigeria’s fragile economic recovery or push it closer to alternative trading partners like China.

The Biden administration has carefully calibrated its public statements on Nigeria’s import bans to avoid appearing heavy-handed while still protecting American economic interests. During her visit to Abuja in November 2023 Vice President Kamala Harris emphasized America’s commitment to supporting Nigeria’s industrialization goals but stressed the importance of maintaining predictable trade rules for foreign investors. This balanced messaging reflects Washington’s awareness of Nigeria’s strategic importance in Africa and the need to preserve broader diplomatic relations beyond immediate trade concerns.